[cmamad id=”5534″ align=”center” tabid=”display-desktop” mobid=”display-desktop” stg=””]

We’re all used to thinking about bacteria in set terms.

We think of bacteria as the causes of disease and other problems.

But bacteria have their own problems.

And these problems may be keeping us alive.

Think of it like this nursery rhyme.

Big fleas have little fleas,

Upon their backs to bite ’em,

And little fleas have lesser fleas,

and so, ad infinitum.

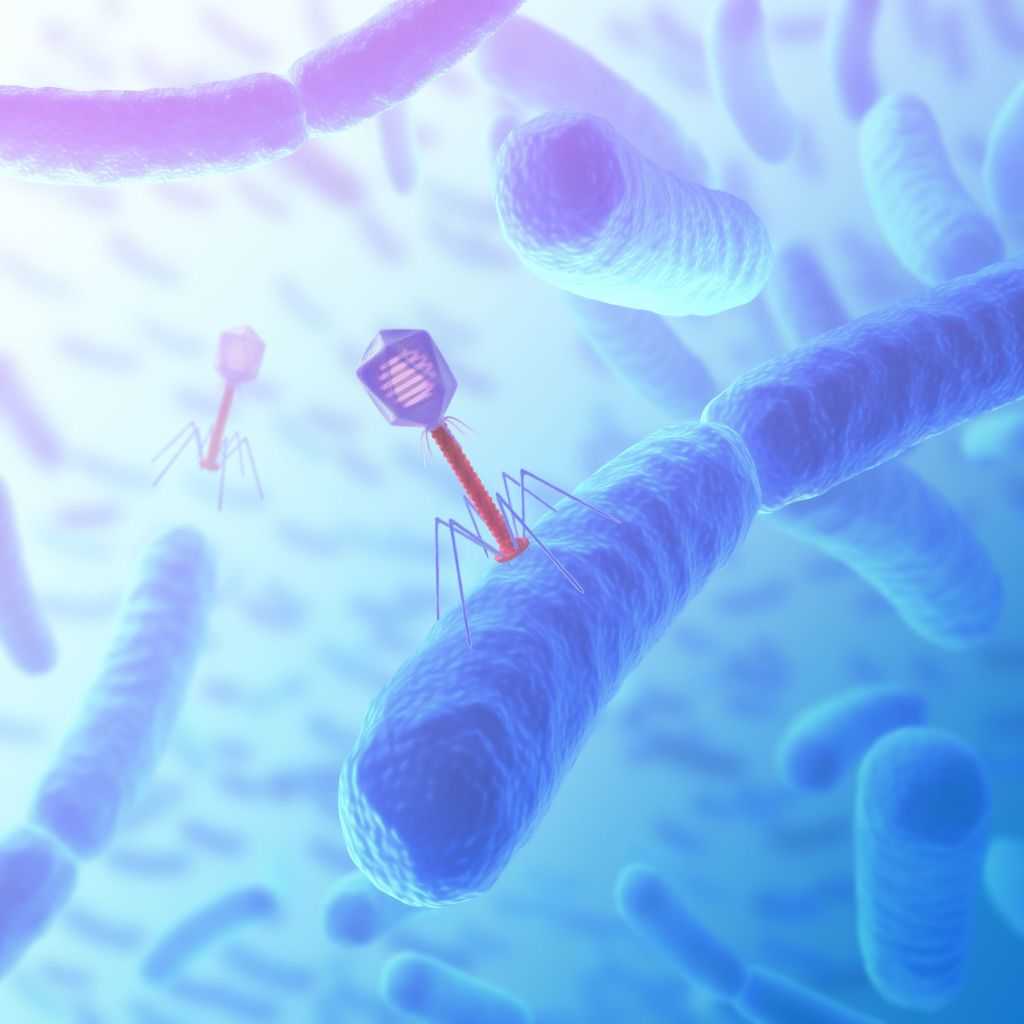

Today, I’m talking about what are called bacteriophages, or phages.

Phages are viruses that prey on bacteria.

[cmamad id=”5535″ align=”center” tabid=”display-desktop” mobid=”display-desktop” stg=””]

They are the littlest “fleas,” but they are probably the major thing that keeps bacteria controlled.

And they control the bacteria in the environment, too.

So they’re pretty important.

They’re potentially so important that doctors look for ways to use these to treat illnesses.

Researchers conduct phage therapy clinical trials and other research to look for applications.

One of the puzzles of the day is why fecal transplants work.

Someone who has a strong gut and strong health will defecate into a jar.

The feces gets processed, perhaps dried, and put in the capsules.

Then a trusting and willing friend or family member swallows the capsule with the hope that it will help.

That person may have severe arthritis, irritable bowel syndrome, or even Alzheimer’s.

And after swallowing that fecal pill, they can mysteriously get a lot better!

This is what is euphemistically called a “fecal transplant.”

I believe that each person has their own set of bacteria and their own set of phages in their body.

And the phages are what are keeping the bacteria in check.

If you’re continually sick or infected, you may need to increase or change the phages in your body.

There’s going be a lot of study on phages, and they are the next huge frontier and medicine.

This University of Pennsylvania study has some answers:

So first, researchers collected fecal matter from six study subjects.

They attempted to purify this fecal matter to find “virus-like particles.”

The study subjects were all people who were healthy and had not been given antibiotics for a while.

Then the researchers had these people go on certain diets.

Two individuals were fed a high-fat/low-fiber diet, three were fed a low-fat/high-fiber diet, and one was on a “whatever you want” diet.

Then they collected stool samples from these volunteers who have been on these diets.

And they purified them.

Now we’re very limited when we study viruses today.

People believe that viruses can be isolated, or the viruses are viewable under an electron microscope.

But the reality is that it is very difficult, sometimes even impossible to isolate viruses.

And it is very difficult to look at something under a microscope and know that it is a particular virus.

So in this study, like every other study, what the researchers do is they look for DNA that MAY belong to viruses.

Then they decide to “amplify” this DNA using PCR technology, and they assume that this DNA belongs to viruses.

That said, here are some startling conclusions from the study.

First of all, viruses work by injecting their DNA into a cell.

In the case of phages, they inject their DNA into a bacterial cell.

However, normally you expect a “boom and bust” cycle like what happens with human illnesses.

You expect lots of viruses infecting lots of bacteria cells — a massive amount of dying bacteria.

And then you’d expect to see a reduced population for a while.

But this did not happen.

It turns out that the phage and bacteria population is quite stable in our gut.

Bacteriophage and bacterial abundances did not oscillate detectably over the time period studied.

The set of viruses in each person was fairly stable.

However, each person has their own unique phage population, different from other people on the same diet.

It doesn’t seem that phages are acquired when we eat our food.

We might acquire them from our mothers.

And it’s possible that we can acquire them through the fecal transplant that I explained earlier.

It may be that the benefit of fecal transplants is really about phages.

If you have phages that kill harmful bacteria, and I don’t have those phages, then I may suffer from those harmful bacteria.

But, if I get some of your feces which contains those phages, it’s possible I may be able to treat the harmful bacteria.

The “imported” phages are going to kill the harmful bacteria and make me better.

Now, phages can be somewhat influenced and changed by diet.

I believe that dramatic changes in body temperature can also change them.

I think if you’re warmer, you have a very different set of bacteria and phages.

And this may favorably lower your chances of getting infections and even cancer.

So, are phages the new probiotic?

Maybe.

You can actually buy phages now and eat capsules containing phages.

Life Extension offers them, and so does another company.

These may be an important, useful thing to take for people with gut inflammation.

Each compound is said to include a handful of useful phages and some gut bacteria found to be helpful.

I’ll keep you more posted on phages and supplements containing phages as the story unfolds.

If you have recurring gut problems, you may want to look into these phage-containing supplements.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3202279/

Leave a Reply